Click for More Articles

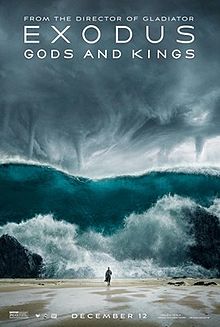

Exodus Gods and Kings

A Life of Moses: A Film Directed by Ridley Scott

By Duncan Roper

This film opens with scenes of great building projects taking place in Egypt. Along with the finished and part finished buildings are people in bondage subject to the lash of their overseers. Those making the bricks, hauling them to where they need to be placed and erecting them into position - all under the lash of their overseers are - of course, the Hebrew slaves. The numerous descendants of Joseph and his brothers are now in bondage to ‘a Pharaoh who did not know Joseph.’

The scene shifts to the Royal palace in Memphis, where we learn that the Pharaoh is Seti, father of Ramses the Great (1294-1279 BC). The discussion at the Court is focussed on the build-up of Hittite troops outside the city of Kadesh, just over the border of the territory controlled by Egypt. A high priestess is busy with the entrails of a bird as she endeavours to read an omen from the gods concerning the intentions of the Hittites and the likelihood of success in battle should the Egyptians decide to attack.

The priestess announces that the omens foretold in the entrails of the dead bird are not clear with regard to the outcome of a forthcoming battle at Kadesh. However she goes on to talk of something else that has been made very clear in them: ‘In the battle against the Hittites, a leader will be saved and his saviour will one day lead.’ A man, yet to be identified, then says ‘that taking notice of this would imply we should all then abandon reason and listen to the guidance of omens.’

Preparations are made for the leading of the Egyptian army under the command of two men - the one who has just made this comment regarding reason and omens, as well as his immediate superior. The Pharaoh presents each of them with special guilded swords that he specifies are for the protection of the one by the other. We then learn that these two men – as cousins - were brought up like brothers in the household of the Pharaoh. One was to become the next Pharaoh - Ramses II, called ‘the Great;’ the other was to become the leader of the Hebrew liberation from Egypt, Moses.

The depiction of Moses’ early scepticism regarding omens is not shared by the Egyptian Pharaoh, his son Ramses or indeed any of the Egyptians. This means that the message of the omen regarding ‘the saving of the leader at Kadesh, with the saviour one day becoming a leader, is understood by Ramses as his being passed over as the future Pharaoh by this saviour in the forthcoming battle. He therefore instructs Moses to ‘turn the other way’ should he see Ramses threatened at the forthcoming battle at Kadesh.

Nonetheless, Moses does save the life of Ramses in the course of the battle, and although he dismisses any significance to it, this is not the view of Rameses and his father, Seti. Once they are back in Memphis, Seti is suspicious as he receives confused and empty replies to his questioning concerning the forecast of the omen. He gets more from his questioning of Moses than from anyone else and it becomes apparent that he has a higher regard for the character and integrity of Moses than his own son. This then opens up the way for the story to take a turn towards acquainting us with Moses’ discovery of his Hebrew identity, and his subsequent banishment from Egypt, the finding of his way to the land of Midian, thus seeming to put the threat posed to Ramses by Moses’ situation in Egypt to one side. Its meaning, however, is very different to what was understood by Ramses. As onlookers, we know that Moses is to become the leader of the Hebrew liberation from Egypt, a much more serious threat to the life of Egypt.

This opening sequence is very pertinent to understanding the ethos of the film in more ways than one. Going back in our history two hundred years, before the full implications of the discovery of the Rosetta stone in the Nile Delta had begun the unlocking of our knowledge of the history of ancient Egypt, the events of the Exodus related in the Biblical narrative were not considered all that problematic. Today, however, things are very different. There may be many ways in which archaeological discoveries have both clarified and amplified the Biblical accounts of Ancient Near Eastern history. However, the evidence concerning the story of the Exodus outside of the Bible, is meagre; so much so that some schools of Biblical Scholarship – the so-called ‘minimalists’ - actually discount its historicity altogether. Whilst the details of this discussion need not concern us here, I refer the reader to the footnotes where she or he may want to follow them through.

In this respect, the early contrast in the film between the Moses’ character’s ‘belief in reason’ and the Egyptian ‘belief in omens’ is paralleled by the modern belief in reason/science/scholarship and its scepticism toward the ‘super-naturalism’ of the Biblical account. This is particularly the case as it was presented in the two Cecil B DeMille films (1923 and 1956) each entitled The Ten Commandments. These were ostentatious blockbusters, with the 1956 film being the most expensive film ever to that date that, at the same time, was the film with the highest box office return of that year.

It is undoubtedly this expensive and shallow religious ostentation, supposedly in an authentic following of the Biblical text that is partially responsible for the following regarding the general historical authenticity of the Biblical story in an essay by the Biblical scholar, Norman Gottwald:

Discussion of the origins of early Israel inevitably entails the problematic historicity of the exodus from Egypt and conquest of Canaan. The biblical traditions in Exodus through Judges that recount these events are permeated with the grandiose iconic style of legend, and, if taken as actual history, describe happenings and beliefs that are anachronistic or implausible. Significantly, apart from the Bible, there is no mention of these events, and they are incongruent with what we do know of that period of Egyptian history from ancient written sources and from archaeology.

However, that this author wants to affirm the significance of the overall Exodus story as is evident from his succeeding remarks:

Nonetheless, the biblical tradition about the Exodus is to be taken seriously as a symbolic projection that affirms Israel’s exciting, going forth, form imperial oppression in Canaan. Likewise, the conquest of Canaan is a symbolic projection of Israel’s coming to independent self-rule in the highlands of Canaan.

This creates something of a problem. If the Bible does endorse the idea of an Israelite deliverance from slavery by God, then how does it happen? I confess that, upon my first viewing of Exodus: Gods and Kings with its initial attempt on the part of Moses to initiate a guerrilla war against Egypt by his makeshift Hebrew army, I thought that we were in for a solution to this problem that involved the kind of violent insurrection typified by the story of Spartacus. However, such a judgment was premature and I was proven quite wrong, so much so that the film does actually present the possibility of an interesting solution to this kind of problem.

When we read the early account of the Moses story in the book of Exodus, we can easily attribute an unwarranted degree of depth in the content of Moses’ understand-ing of the Hebrews. The film, however, introduces us to a Moses who, at least initially, is much more Egyptian than Hebrew. At the same time, somewhat mysteriously connected to his (unknown at this point) Hebrew identity, Moses is very sceptical regarding many of the features of the traditional Egyptian worldview. It all begins to fall into place after Moses’ visit to the slave city, Pithom, on behalf of Pharaoh Seti, where he meets with a group of Israel’s elders. One of these is Nun, Joshua’s father (played by Ben Kingsley), who speaks with Moses, disclosing the basic details of the story of his identity. The various pieces then begin to make sense to him, leading him on a journey of discovery into his own identity and his calling from the God of his fathers.

However, they are overheard by two other Hebrews who then convey the news of Moses identity to the Egyptian official who exercises an ostentatious rule of the city. He, in turn, passes the information on to Rameses, who has recently become Pharaoh. A crisis arises in which Moses decides to throw in his lot with the Hebrews, thereby incurring the wrath of the ‘queen mother’ who wants Moses dead. Ramses settles on sending Moses into exile – to the point of supplying Moses with the sword given by Seti to protect him, hidden in his luggage.

After fending off the attacks of two assassins, Moses makes his way to Midian, where the events of the Biblical story of Exodus 2:15-23 are acted out very effectively. We are then introduced to a very interesting innovation concerning the way in which ‘the angel of the Lord’ mentioned in Exodus 3:2, is deemed to speak to Moses at the burning bush. Putting aside all the bombastic grandeur associated with Cecil D de Mille’s The Ten Commandments, the message of God concerning the plight of the Hebrews is spoken to Moses – as he has been caught in the midst of a mud-slide covering his whole body except for his mouth, eyes and nose – through a very unusual boy of around ten years old. He has the name Malek (meaning Messenger) and throughout the remainder of the film, this character – as a messenger of God – speaks with Moses regarding the unfolding of God’s plan for delivering the Hebrews to Canaan (or at least) that section of the journey that concludes at Mount Sinai.

Thus we are prepared, after the depiction of Moses efforts to gain Hebrew freedom through beginning a guerrilla war against the Egyptians, for Moses second meeting with Malek, who this time chastises him for his stupidity, telling him that his job, for the moment, is just to watch. This introduces the plagues, with the Nile turning to blood as the result of huge numbers of crocodiles taking their toll on the Egyptian populace, in ways that open up the way for the other plagues. Before the final plague of the death of the first born, Malek meets up again with Moses. After receiving this news, Moses goes again to Ramses, pleading with him (rather than threatening him) to let the Hebrew people – pointing out the extent of the pain the Egyptians would all suffer if he were to refuse. Next morning, grief-stricken at the death of his baby-boy, Rameses gives the word to let the Hebrews go.

Thus the story of the actual journey of the Israelites from the city of Pi-Ramses in the Eastern Nile Delta region of Goshen to Mount Sinai, begins. Of the many options to the location of Sinai, the film favours its location in Midian, near the coast of the eastern side of the Gulf of Aqaba in Arabia today. (The text of the Bible speaks of Mount Horeb as close to or in Midian, and Horeb is usually identified with Sinai.) On his first journey to Midian, Moses went to the south of the Sinai Peninsula going across the Straits of Timur before going north to Midian. Although initially following this path to Sinai, Moses elects to take a root through the mountains that leads the Israelites to a place on the Western coast of Aqaba, where they are cornered by the mountains, the sea and the oncoming Egyptian army led by Ramses. It is at this point that Moses’ faith in the God of the Hebrews is clinched. In the confidence of this faith, he leads the people into the shallow waters of the great parting of the sea that God provides for their deliverance. The Egyptians, on the other hand, fall victim to the wrath of the seas returning to normal as God delivers Israel from the bondage of the Egyptians.

Moses is then reunited with his Midianite family, who join the Hebrew people as they then proceed to Mount Sinai, and the film concludes with Moses chiselling the text of the Ten Commandments on the stone tablet, in the company of Malek.

Based on the way that the text of Exodus depicts Moses engaging in discussions with God – a feature that indicates that Moses was not exactly a passive ‘medium’ in the writing of the details of the body of law forming the basis of the Torah – it is not far-fetched to think of God’s will for the future national life of Israeli being worked out in a way that entails the covenantal relationship between them being initiated by God. At the same time, the unfolding of its details could well have been partly the result of the work of a sophisticated man, brought up and educated in the ways of the wider Ancient Near East, shaping the form of the Sinai covenant as a bond between YHWH and Israel that reflected many of the ANE features while, at the same time, differing substantially with its dominant overall Kingly and pagan patterns.

It is in this vein that the Egyptologist, Kenneth Kitchen, in his book The Reliability of the Old Testament, pictures an initial thoroughly Egyptian Moses being brought up as ‘as a graduate of the Pi-Ramesses foreign ministry, and from his days in the foreign-office ministry, aware that every other people group and state had a sovereign ruler - a king who was often a deity’s representative – was able to draft a pattern of law and treaty/covenant as the basis for regulating the community life of the nation of Israel under the Kingly rule of her God.’

Thus, the thorough Egyptian background of Moses would have provided a basis for the writing the outline and detail of a Covenantal arrangement of YHWH in the role of a King over his people. This would have been able to provide the basis for both individual Hebrews, as well as their various social collectives – families, marriages, farming communities, prophets, priests and political and judicial leaders – as responsible contributors to a way of life that was simultaneously the outworking of the service and worship of YHWH and an outworking of high degree of their own humanity in the faithful realisation of the complex range of offices set out in the various forms of the Sinai covenant.

One of the principal differences between the Egyptian (and wider Ancient Near Eastern) pattern of civilization was the way in which the Pharaoh, as king and god, was related to the panoply of gods on the one hand, and to the wider body of the people on the other. The Pharaoh – once enthroned as such – was on a level with the gods, charged with the responsibility of maintaining maat (law, order, wisdom, balance) of the whole social order in relation to the cosmos. In like manner, as the divine figure amongst his fellow Egyptians, the Pharaoh was the representative of the gods in their midst. The Covenant of YHWH with Israel on the other hand, entailed relationship between God and humans with a much greater degree of equality. God’s covenant was both with the people of Israel as a whole and with each of its individual members. This meant that there was to be no single representative of God’s rule over the cosmos (ie Neither the King nor the High Priest) within the context of their social order. Everyone – through the various offices they held – worshipped and served the Lord within the context of the Sinai covenant – that should be understood as renewal and revivifying of the original covenant with all humankind.

This had huge implications for the contrast that should exist regarding the material culture of an Israelite king, should the people desire to have one. Thus we read in Deuteronomy 17 the following:

When you come to the land which the Lord your God gives you, and you possess it and dwell in it, and then say, “I will set a king over me like all the nations round about me’; you may indeed set as king over you him whole the Lord your God will choose. One from among your brethren you shall set as king over you; you may not put a foreigner over you, who is not your brother. Only he must not multiply horses for himself, or cause the people to return to Egypt in order to multiply horses, since the Lord has said to you, ‘You shall never return that way again.’ And he shall not multiply wives for himself, lest his heart turn away; nor shall he greatly multiply for himself silver and gold.

This should be is enough to point us in the direction of a significant feature of the overall purpose of God in the vast scope of the event that we call the Exodus. It was for the benefit of the liberation from slavery for the personal benefit of the individual Israelites. However, it was much more than that. It was part of the overall redemptive initiative of God in bringing humanity back to spiritual and social health through the people of Israel. The paganism of Egypt meant privilege and prosperity to the Pharaoh and to those in his immediate service – including the priesthoods of the various deities, their temples and lands.

In Summary.

The film Exodus: Gods and Kings does not try to stick to all the details of the Biblical narrative. Rather it tries to bring the epic story of Moses as a very significant figure of human history, alive to us. To do this Moses is pictured, at least initially, as an Egyptian member of the Royal house, who slowly comes to appreciate his kinship with the Hebrew people in the particulars of their relationship to their God. The process of the development of his understanding of his Hebrew identity and his coming to know the Lord as Covenant God so that he is able to place his faith in him in the life or death situation of their being caught between the mountains, the sea and the army of the Egyptians, is the basic stuff of the film.

In this respect, the film does capture much of the ambiguity entailed with the secularism of our age. This is typified by the hankering after a real nostalgic faith in relationship to a profound sceptical distrust of easy and worn-out answers. It should therefore provide a good starter to a discussion with a whole range of people on the subject matter of the Bible.

In addition, it just begins to open up the much deeper and broader significance of the Exodus story. Indeed, the latter cannot properly be understood except for its connections with Genesis 1-3, the calling of Abraham and the story of Joseph in Egypt. Moreover, it does not finish at Sinai. The whole purpose of the events depicted in the first half of the book of Exodus is with regard to the details of this Sinai covenant in relation to the future life of Israel, and its calling to a very important pointer to the full redemption of humanity in the precepts of social order just hinted at by the above reference to the calling of a king in Israel, should the people decide to have one. Suffice to say that all of this is of considerable importance for a Reformational Christianity worthy of the name.

This is a mockup. Publish to view how it will appear live.