Click for More Articles

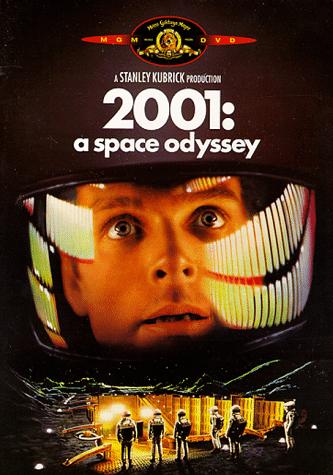

2001: A Space Odyssey

A 1968 Film by Stanley Kubrick

Introduction

By Duncan Roper

2001: A Space Odyssey is a film that was first released almost fifty years ago. Amazingly, it has lost little of its impact over that time. Indeed it has proved to be is a pioneering venture at many levels of cinema history. Movies like Star Wars, The Lord of the Rings and many others have been strongly influenced by its special effects – whether directly or indirectly. Since its premiere in 1968, it has been analysed and interpreted by multitudes of people ranging from professional movie critics to amateur writers and science fiction fans. Both the director of the film, Stanley Kubrick, as well as his co-scriptwriter, Arthur C. Clarke, wanted to leave the film open to philosophical and allegorical interpretation, purposely presenting the final sequences of the film without the underlying thread being apparent; a concept illustrated by the final frame of the film, which contains the image of the embryonic ‘Starchild.’

However, neither of these two men behind the film equated openness to interpretation with meaninglessness. When he claimed that ‘If anyone understands it on the first viewing, we've failed in our intention,’ it might have seemed that Clarke implied something like this. When told of the comment, Kubrick said that ‘I believe he said this facetiously. The very nature of the visual experience in 2001 is to give the viewer an instantaneous visceral reaction that does not—and should not—require further amplification.’

These two points are not necessarily contradictory. An aesthetically rich telling of any complex and multilayered story takes a good deal of digesting. On the one hand, the richness of the aesthetics can very often affect those experiencing it at a deep emotional and intuitive level – giving an ‘instantaneous visceral reaction that does really requite any explanation.’ On the other hand a complex and multilayered story often has a basic plotline level that may well be grasped at some basic level of an initial experience. However, in order to grasp the depth of its various layers of meaning, a measure of analysis and repetition of the experience is required.

Kubrick has said that his main aim was to avoid ‘intellectual verbalization’ and try to reach ‘the viewer's subconscious.’ However, this was not done with a deliberate attempt to strive for ambiguity. Rather, it followed from his intent of making the film ‘nonverbal,’ with a minimal use of dialogue. He was then willing to give a straightforward explanation of the plot on ‘the simplest level,’ but did not want to discuss any ‘metaphysical interpretation of the film.’ He left this up to the individual viewer. Hence, before later discussing a possible meaning of the film more analytically, in our preliminary account of the film we shall attempt to recap this original intent of its makers.

2. The Film

The film opens with a very brief overture, one that is extremely arresting: the opening bars of Richard Strauss’s Tone Poem on Nietzsche’s Also Sprach Zarathustra (Thus Spake Zarathustra). This then introduces the reddish discs of the light the of the sun reflected from the moon onto an earth cast into the contrasts of light and shadow that then forms a background for the title of the movie – 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The Dawn of Man

This gives way to the sounds of birds as they accompany a sequence of still shots that carry on the theme of reddish light at dusk – with plains in the foreground and mountains at the back. Early in this sequence we read the caption The Dawn of Man. To the low level bird sounds a comparable level of whirling wind sounds are added. The reddish tinge of light to the stills then gives way to fuller daylight. Our first glimpse of life is then conveyed by means of the dead skull of a cow followed by a more comprehensive picture that includes other bones.

The images shift to moving shots of apes and tapirs grazing on plants. The sounds are those of the apes objecting to the tapir attempting to steal their food. There is also a shot of a leopard standing over its prey of a dead zebra; and there is another of a leopard attacking an ape. One group of apes is in possession of a water hole, shouting out their rights as a possible warning to other groups. One such group does indicate its intention to oust them but fails in its attempt to shout them away. The scene shifts to night sleep and the quarrelsome vigil of the apes. After a brief glimpse of a red sky at night, it is morning and one of the apes gets agitated at the sight of something and shouts at it - waking the others to an imitation of its stamping and shouting.

We then get a full shot of just what has caused the fuss. It is a rectangular black monolith that has somehow been placed into the ground, standing up striaght. The apes continue their shouting and jumping ritual but new sounds are heard. This is the music of the Dies Irae movement of G Ligeti’s Requiem. As the ape clan gathers round it, jumping and touching the monolith, the sounds of the shouting and stamping of the apes fade, leaving the revelatory transcendence of the music together with an orbital conjunction of the sun, earth and moon declaring that something profound and out of the ordinary is going on.

Suddenly all sounds cease and we are once again confronted with a sequence of still shots that also mark a return first to the earlier bird sounds, followed by the low-level swirling wind sounds that then lead us back to the ape clan. One of them, in the midst of the skeleton remains of one or two animals, gets hold of a large femur bone and starts to use it to cause other bones to jump up and make mayhem. We catch a brief glimpses of the monolith and the shot of the earlier orbital conjunction of the sun, earth and moon before the ape is somehow prompted to smash the skulls of these skeletal remains of the animals. In the midst of all this we once again hear the opening bars of Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra, while we see a tapir fall to the ground dead, no doubt with the help of one or more of the bones wielded by the apes. Except for the natural sounds of the apes eating and moving around we watch as first one ape and then the whole clan have now turned form the eating of grass, to the eating the meat of slain tapir. In the meanwhile other tapir continue to graze nearby. We then see a repeat attempt on the part of this ape-clan to oust their rivals from the water-hole. This time the attacking ape-clan has a ‘technological edge.’ They have learned not only how to use bones as weapons. They have also learned how to kill and maim their opponents. They kill they leader of the rival ape clan, frighten off the others, and claim the water hole for themselves.

Part I ends with the ‘ape-man’ throwing the femur-bone weapon spinning high into the air, prefiguring the spaceship of the second part of the film as it falls to earth. There is a huge time period – millions of years - between Parts I and II

In Part II, we are introduced to images of space, the giant wheel of a partially built space station in orbit above the earth. All these images are accompanied by Johann Strauss the younger’s famous waltz tune ‘The Blue Danube’ played by full orchestra. This scene, together with the music, also includes a mostly empty transport PAN AM plane carrying someone form earth to this space station. The music of The Blue Danube ceases at the docking of the PAN AM flight at the space station. The brief silence is broken by the first human dialogue in the film. When it comes, it brings us ‘down to earth with a bump’.

The main person on board the shuttle to the space station is Dr. Heywood R. Floyd. He is to continue his journey to Clavius Base, a United States outpost on the moon, the following day. After a video phone call with his daughter, Floyd's Soviet scientist friend and her colleague ask him about rumors of a mysterious epidemic at Clavius. Floyd says that he is not at liberty to discuss the matter. At the conclusion of the conversations between them, the music of The Blue Danube resumes. We join Floyd onto the moon and the base at Clavius. The music again finishes with the docking of the space craft. We are abruptly transferred to a meeting between Floyd and the heads at the American base Clavius. After his introduction, it becomes apparent that Dr Floyd is someone of standing in the whole setup. He knows all about the situation, and simply pretended a degree of ignorance concerning it at the space station. He apologizes for the epidemic cover story and then goes on to further stress the need for secrecy. His mission in this respect, is to investigate a recently found artifact that appears to have been deliberately buried beneath the surface of the moon some four million years ago. Floyd and others ride on a Lunar Shuttle to visit the artifact, where it becomes evident that it is a monolith almost identical to the one encountered by the man-apes in Part I.

We then return to the scene of the lunar landscape and the ill-lit sky. The music resumes, but it has a much more transcendent quality about it than The Blue Danube. It is J. Ligeti’s Lux Aeterna. This sense of transcendence is maintained while the Lunar Shuttle transports us over the ill-lit, but wonderful scenes of the lunar landscape. As the music fades we are again brought down to an earthly bump by the human needs for food as everyone gets ready for the next ‘transcendent part’ of the adventure.

As the music of Ligeti’s Lux Aeterna returns - guiding us to the landing of the Lunar Shuttle, the incredible character of the contrasts between the dark background of space and the low intensity of the light on the moon, serves to emphasize the coming invasion of transcendence into the common world of secularized humanity. As we are made aware of the excavated lunar landscape, the music changes. It is still Ligeti. However, we return to the Dies Irae movement of his Requiem that accompanied the first appearance of the mysterious monolith amongst the apes in Part I. As the men, all clad in their lunar suites, descend down the path to the lower part of the excavation, we catch a glimpse of the monolith. Just as the apes before them had touched the monolith, so too do this group of astronauts. This time around, however, there are no jumps of joy and delight, no shouts and screams. Indeed, after having their group photo taken in front of it, the monolith emits a piercing sound that all bur deafens the astronauts. At the same time we have a brief glimpse of the conjunction between light and darkness with the conjunction of the earth moon and sun, this time from the darkness of the moon.

The Jupiter Mission

We then move forward in time a further eighteen months. The caption on the screen reads Jupiter Mission: 18 months later. The images are of both the exterior and the interior of a space craft. The rich strains of the legato strings playing the Adagio of Khatchaturian’s Gayaneh accompany both the interior and exterior shots.

The U.S. spacecraft Discovery One is bound for Jupiter. On board are the mission pilots and scientists Dr. David Bowman and Dr. Frank Poole, together with three other scientists in cryogenic (deep sleep) hibernation. Most of Discovery's operations are controlled by the ship's computer, HAL 9000, referred to by the crew as ‘HAL.’ Bowman and Poole watch a TV news clip of HAL and themselves being interviewed, on the BBC, about the mission. In the course of this, HAL states that he, along with other such computers, is ‘foolproof and incapable of error.’ When asked by the host if HAL has genuine emotions, Bowman replies that he appears to, but that the truth is unknown.

Khatchaturian’s music continues with features of dialogue superimposed until HAL initiates a long conversation with Dave. In it he reveals the extent of his human qualities for worrying about a whole range of features surrounding the mission that seem to him very odd. He endeavours to engage Dave in these matters, but it is just not clear whether or not Dave is aware of them. This is followed by HAL’s report concerning an imminent failure of an antenna control device. With the soundscape dominated by the simulation of an astronaut’s deep breathing accompanied by a low-intensity and medium to low pitched humming sound, the astronauts retrieve the component with an EVA Pod (a small space craft capable of moving in and out of the main ship), but find nothing wrong with it. HAL suggests reinstalling the part and letting it fail so that the problem may then be quickly diagnosed. Mission Control, however, advises the astronauts that results from their twin HAL 9000 backups indicate that HAL is in error. The conversation between HAL, Dave and Frank then goes like this:

HAL: I hope the two of you are not concerned about this.

Dave: No, I'm not HAL.

HAL: Are you quite sure?

Dave: Yeah. I'd like to ask you a question, though.

HAL: Of course.

Dave: How would you account for the discrepancy between you and the twin 9000?

HAL: Well, I don't think there is any question about it. It can only be attributable to human error. This sort of thing has cropped up before, and it has always been due to human error.

Frank: Listen HAL. There has never been any instance at all of a computer error occurring in the 9000 series, has there?

HAL: None whatsoever, Frank. The 9000 series has a perfect operational record.

Frank: Well of course I know all the wonderful achievements of the 9000 series, but, uh, are you certain there has never been any case of even the most insignificant computer error?

HAL: None whatsoever, Frank. Quite honestly, I wouldn't worry myself about that.

Dave: Well, I'm sure you're right, HAL. Uhm, fine, thanks very much.

Thus, HAL insists that the problem, as with all previous issues with the HAL9000 series, is due to human error. Concerned about HAL's behavior, Bowman and Poole enter an EVA pod with the sound turned off, to talk without Hal overhearing, and agree to disconnect Hal if he is proven wrong. HAL, however, secretly follows their conversation by lip reading. Their conversation goes like this:

Frank: I've got a bad feeling about him.

Dave: You do?

Frank: Yeah, definitely. Don't you?

Dave: I don't know. I think so. You know, of course though, he's right about the 9000 series having a perfect operational record. They do.

Frank: Unfortunately, that sounds a little like famous last words.

Dave: Yeah. Still, it was his idea to carry out the failure-mode analysis, wasn't it?

Frank: Hm.

Dave: Which should certainly indicate his integrity and self-confidence. If he were wrong, it would be the surest way of proving it.

Frank: It would be if he knew he was wrong.

Dave: Hm.

Frank: But Dave, I can't put my finger on it, but I sense something strange about him.

[HAL watches them speak, reading their lips]

Frank: Let's say we put the unit back and it doesn't fail, huh? That would pretty well wrap it up as far as HAL is concerned, wouldn't it?

Dave: Well, we'd be in very serious trouble.

Frank: We would, wouldn't we?

Dave: Hmm, hmm.

Frank: What the hell can we do?

Dave: Well, we wouldn't have too many alternatives.

Frank: I don't think we'd have any alternatives. There isn't a single aspect of ship operations that's not under his control. If he were proven to be malfunctioning, I wouldn't see how we would have any choice but disconnection.

Dave: I'm afraid I agree with you.

Frank: There'd be nothing else to do.

Dave: It would be a bit tricky.

Frank: Yeah.

Dave: We would have to cut his higher-brain functions...without disturbing the purely automatic and regulatory systems. And we'd have to work out the transfer procedures of continuing the mission under ground-based computer control.

Frank: Yeah. Well that's far safer than allowing HAL to continue running things.

Dave: You know, another thing just occurred to me...Well, as far as I know, no 9000 computer has ever been disconnected.

Frank: No 9000 computer has ever fouled up before.

Dave: That's not what I mean...Well I'm not so sure what he'd think about it.

At this point the movie has a caption entitled INTERMISSION. This entails a black screen accompanied by an almost three minute long passage of electronic music. It is broken by the sounds of astronaut deep breathing together with external scenes of Discovery One with Frank in a pod moving toward that part of the ship where he would replace the unit in a spacewalk.

The consequences of Frank Poole’s and Dave Bowman’s failure preventing the almost omniscient HAL from learning of their suspicions and plans, begins to have serious consequences. Poole’s attempts to replace the unit during a spacewalk are thwarted by HAL’s severing of his oxygen hose and setting him adrift in space. Bowman takes another pod to attempt a rescue, but leaves his helmet behind. HAL then turns off the life support functions of the crewmen in their hibernation of suspended animation. When Bowman returns to the ship with Poole's body HAL refuses to let him in, stating that the astronauts' plan to deactivate him jeopardizes the mission. Bowman then opens the ship's emergency airlock manually. Upon entering the ship, he proceeds to HAL's processor core to disconnect the computer. HAL tries to reassure Bowman, and then pleads with him to stop. Finally he expresses fear. As Bowman deactivates the circuits controlling HAL's higher intellectual functions, HAL regresses to his earliest programmed memory, the song ‘Daisy Bell’ which he sings for Bowman.

When HAL’s ‘higher functions’ are finally disconnected, a pre-recorded video message from Floyd reveals the significance of the buried monolith discovered on the surface of the moon: its purpose and origin still unknown. With the exception of one short, but extremely powerful radio emission aimed at Jupiter, the action that had preceded the depiction of the Jupiter Mission, the monolith object has been inert.

Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite

The final Part of the Movie is introduced by the caption: Jupiter: And Beyond the Infinite. Although what is happening, in this part of the movie, is not altogether clear, we might fill in with some of the more doubtful details as follows: Once in Jupiter space, Bowman leaves Discovery One in an EVA pod to investigate whether another monolith might be in orbit around the planet. The pod is pulled into a vortex of colored light, and Bowman races across vast distances of space, viewing bizarre cosmological phenomena and strange landscapes of unusual colors. The music of this part is all drawn from Ligeti: Dies Irae from Requiem; Atmospheres: Lux Aeterna; and Aventures. Together, they bear witness to the evocation of a transcendence, a mystery, a hope in the unknown future.

We end up in the classical style of Louis XVI’s rooms. We encounter Bowman’s successively aging doubles – one in a space suite; the next at the table dining and then in the deathbed, before the final appearance of the monolith. As the dying Bowman reaches for it, he is transformed into a fetus enclosed in a transparent orb of light. As the focus of the shot switches to the monolith at the foot of the bed, we hear once again the introductory bars of Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra. The film ends as this new being floats in space beside the Earth, gazing at it.

A recap of Johann Strauss, the younger’s The Blue Danube accompanies the Credits.

3. The Meaning of the Film

Kubrick was a legendary American film director, producer, and screenwriter. He is responsible for some of the most famous films of all time, including 2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange, Paths of Glory, Lolita, Dr. Stangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, and Eyes Wide Shut, among many others.

--

In an interview Kubrick once said that ‘2001 gives a little insight into my metaphysical interests... I'd be very surprised if the universe wasn't full of an intelligence of an order that to us would seem God-like. I find it very exciting to have a semi-logical belief that there's a great deal to the universe we don't understand, and that there is an intelligence of an incredible magnitude outside the Earth. It's something I've become more and more interested in. I find it a very exciting and satisfying hope.’

In another interview he stated that ‘I will say that the God concept is at the heart of 2001 but not any traditional, anthropomorphic image of God. I don't believe in any of Earth's monotheistic religions, but I do believe that one can construct an intriguing scientific definition of God, once you accept the fact that there are approximately 100 billion stars in our galaxy alone, that each star is a life-giving sun and that there are approximately 100 billion galaxies in just the visible universe. Given a planet in a stable orbit, not too hot and not too cold, and given a few billion years of chance chemical reactions created by the interaction of a sun's energy on the planet's chemicals, it's fairly certain that life in one form or another will eventually emerge.

It's reasonable to assume that there must be, in fact, countless billions of such planets where biological life has arisen, and the odds of some proportion of such life developing intelligence are high. Now, the sun is by no means an old star, and its planets are mere children in cosmic age, so it seems likely that there are billions of planets in the universe not only where intelligent life is on a lower scale than man but other billions where it is approximately equal and others still where it is hundreds of thousands of millions of years in advance of us. When you think of the giant technological strides that man has made in a few millennia—less than a microsecond in the chronology of the universe—can you imagine the evolutionary development that much older life forms have taken? They may have progressed from biological species, which are fragile shells for the mind at best, into immortal machine entities—and then, over innumerable eons, they could emerge from the chrysalis of matter transformed into beings of pure energy and spirit. Their potentialities would be limitless and their intelligence ungraspable by humans.’

I want to base my analysis of the meaning firmly in the film itself. I do not think that anyone can deny that the film depends a great deal upon the monoliths that occur at three different places in its unfolding. Neither can it be disputed that the significance of this image, in each of these three cases evokes – particularly in association with the music accompanying it – a real sense of a reality to existence – especially our human existence – that takes us beyond our immediate experience of the world of our everyday experience. If were refer to that world of our experience as ‘secular,’ then the joint symbolism of ‘the monolith’ and Ligeti’s and/or Richard Strauss’s music, may be said to evoke a genuine sense of their being another dimension to reality - beyond the secular. Furthermore, all this would be in accord with the word of Stanley Kubrick just quoted.

With all this in mind, I propose an analysis of the film along the lines of a ‘babushka’ doll with three layers, one for each of the three appearances of the monolith. The appearance of second of the monoliths on the moon, heralding the mission to Jupiter, ending with the destruction of HAL’s higher functions, corresponds with the inmost doll; the first appearance of the monolith with the ape-clan is an outer doll that concludes with the death of Dave Bowman in the neo-classical rooms of Louis XVI. The outermost doll is the child in embryo looking at the earth at the end of the film. It has a beginning, but not an end. We could stretch it a bit saying that its beginning, as a hope of destiny, corresponded with the very appearance of the cosmos depicted in the beginning before the film was even made.

Central to the ‘inner babushka doll’ of this analysis is a human being capable of achieving ends that he or she designs through the making of tools that aid this process. The ape-man did not really make a tool. He simply used a pre-existing bone as a weapon. This may have anticipated the fashioning of a club from wood, stone or bone for that purpose, but tools as we know them, require human labour and design in their ability to be able to assist humans in the process of developing the potential of creation to include houses, wholesome and tasty food as well as many other things.

In the section of the film that follows the ape-man throwing his bone-club up into the air - anticipating the space-ship flying through space - we have confronted a human being who has developed very highly sophisticated tools. These include transport vehicles that require neither roads, tracks, rivers nor ocean. Moreover, they are propelled through space by means of the explosive chemicals that were first used in bombs. They have also developed earlier forms of adding machines into very sophisticated machines that are capable of performing very fast and complicated arithmetical and other logical operations with the aid of coding or language devices that they have designed for this purpose.

Moreover, not only is HAL is a very complex computer. It has been equipped with a human sounding voice that not only communicates the results of its incredibly fast complex logical operations in human language, it is also presented as possessing ‘many higher human functions’ – including emotions and the sense of its own identity and purpose. It is precisely these that are under threat in our ‘first babushka doll.’ As a result, the conflict on board Discovery One – between humans and the computer HAL – is presented as life-threatening to both parties. As such it raises a very central question that goes to the very heart of the meaning of human existence: does our assumption that we somehow have a God-given right and responsibility to exercise an oversight over the earth and its environs imply that we should surrender this responsibility to the tools that we have designed to aid us in this responsibility? Should these complex tools that we humans have designed for the purposes of assisting is in the complexity of managing our Gaia world in the twenty-first century cease to be considered tools? Are our robots and computers to develop into our comrades with rights of their own? Would this seemingly almost modest step then be followed by the more drastic one of their becoming the masters and mistresses of our destiny?

The story of our second ‘babushka doll’ begins with the appearance of the monolith within the world of the apes. It is clear that the meaning of this event for the makers of the film is to be found in the idea that a sophisticated civilization somewhere in this vast universe has visited our earth – possibly with a view to having some influence upon it. This influence is then understood as one of aiding and abetting the overall process of emergent evolution. The immediate consequence for the ape-world was the emergence of weapons in the pursuit of food and in the possession and protection of territory and water resources from others whom they considered as enemies. Moreover, this evolutionary journey has continued until the present. This present, in 1968, was of course one that was dominated by the Cold War. The film, on the one hand, pictures this conflict as subservient to the pursuit of common interests in the form of the international space station. On the other, it is clear that the issues raised by the discovery of the buried monolith are such as to be ones of US security. This kind of conflict may, in many ways, have been put behind us in the twenty-first century. Nonetheless, a new threat of this kind has emerged in the form of international terrorism.

The search for the basics of other life-forms in the cosmos has been a major research topic over recent decades. This is another factor in the hope and expectation of finding other more sophisticated civilizations elsewhere in the universe.

The basic argument for this generally proceeds along the following lines:

There are billions of planets in the universe where biological life could have arisen. The odds of some proportion of such life developing intelligence should also be considered high. Our sun is by no means an old star; its planets are mere children in cosmic age. Hence, if intelligent life forms can emerge on earth, why not elsewhere? In some such instances, intelligent life would no doubt be on a lower scale than our humans. However, when you think of the technological strides that humankind has taken over even just over the past three centuries, it would seem almost inevitable that evolutionary emergence beyond our level has taken place somewhere in this vast cosmos. These may well have progressed from biological species - fragile shells for the mind at best - into immortal machine entities. Then, over the innumerable eons, they might well have emerged from the chrysalis of matter, and transformed into beings of pure energy and spirit.

That this kind of metaphysical or religious interpretation is brought to their film, has been made clear in the way that both Clarke and Kubrick brought together the making of the screen play and the novel – both under the title 2001: A Space Odyssey. The physicist Freeman Dyson, for example, urged those baffled by the film to read Clarke's novel, citing his own experience of it as:

After seeing Space Odyssey, I read Arthur Clarke's book. I found the book gripping and intellectually satisfying, full of the tension and clarity which the movie lacks. All the parts of the movie that are vague and unintelligible, especially the beginning and the end, become clear and convincing in the book. So I recommend to my middle-aged friends who find the movie bewildering that they should read the book; their teenage kids don't need to. [See Wikipedia article: Interpretations of 2001: A Space Odyssey.]

Then, in the light of this orientation to interpreting the film, we might point out that the last appearance of the monolith – entailing the child in embryo looking at the earth – is indicative of the vision of a new chapter in emergent evolution. This third, outside babushka doll, would follow as a consequence of the ways in which we respond to the possibilities of other civilizations - in either the galaxy or the wider cosmos – visiting us either in fact or in our imaginations.

However, it should not go unnoticed that the religiousness undergirding the whole approach taken by both Clarke and Kubrick is one that we have elsewhere in this website described as one that takes its final source of meaning and order of the cosmos in terms of Nature-Freedom. [Refer to Varieties of Religiousness and the Gospel on this website].

I would therefore like to conclude this review of the Kubrick film 2001: A Space Odyssey by considering the possibilities of interpreting it within the religious outlook of Creation-Fall and Redemption.

To begin with the Creation was an event that brought the whole temporal cosmos into being. The big-bang was accompanied by the bringing into being of the law-order of meaning of the cosmos that already envisaged the end from the beginning. This law order was and continues to be multi-layered. As such it entailed a range of aspects to its overall meaning: there were the levels of discrete identity and spatial continuity, of movement and energy, as well as those of biotic functioning, feeling, emotion and sensory life. There were also the levels of the higher meaning associated with emotions, thinking and analysis, cultural formation, language together with social interactions entailing ethical and aesthetic dimensions. There are also the levels of faith-as-belief, economy as the responsibility dealing with abundance and scarcity, as well as justice and fairness.

However, whilst all of the concrete created realities of the things, plants, animals and people that we relate to everyday all exhibit the various properties of these aspects or dimensions of reality, none of them is fully encapsulated in any one of these aspects. The general character of the concrete entities of our cosmos do emerge or evolve from one stage to the next – exhibited in the levels of discrete entities, spatial continuity, uniform movement and energy exhibited in inanimate and dead things. The energy qualified matter of such things – sub-atomic particles, atoms, and molecules, do not exhaust what we might refer to as ‘matter.’ Living things like bacteria, amoebae, plants etc are also comprise ‘matter.’ Whilst chemically composed mainly of very large molecules like DNA and proteins, these comprise ‘living matter’ that, once dead, reverts to the patterns of chemical decomposition that are more chemically characteristic of inanimate matter.

Nonetheless, the subject life functions of living things were not exhibited in the things of inanimate world with which the creation actually began and emerged for the greater time period of its existence to date. The dimension or aspect of life began with creation: the potential for such object functions as food and habitat existed from the beginning. However, the particular life forms with their living subject functions subsequently ‘emerged’ under the guiding and purposeful hand of God. This creation potential was unfolded under the faithful and providential hand of God. This genesis or unfolding of the initial creation proceeded under the providential hand of God, providing it with its meanings, structures and order. This first entailed a jump in the emergence of biotically qualified forms from the pre-existing inanimate ones, and then the jump to sentient and feeling creatures of the animal kingdom. Furthermore, this was all in anticipation of the appearance of human beings (and possibly parallel creatures in other regions of the cosmos) as the creatures complete with ‘the higher faculties’ of emotions, thinking, sacrificial love and the humility to work with and serve both God and other humans. .

Transcendence, as it is variously depicted in 2001: A Space Odyssey, is a genuine level of reality. However, it is not a created level. It goes beyond or above creation, but is yet the level of reality from which the full meaning of the lawfulness of God reigns and orders the cosmos. It is also a mode of reality through which we humans, in the depths of the unitary centre of our being that the Bible refers to as ‘our hearts,’ can know God.

Because of the way in which the creatures who were given free will in their choice to serve and worship God as the vice-regents of the earth and potentially elsewhere in the cosmos (See Romans 4:13), their whole-hearted choice to serve and worship other gods has spawned the reality of the emergence of evil along with the good. It has also spawned other forms of religiousness. Creation as we now find it, is therefore flawed. The image-bearers of God fall well short of their calling to serve and worship God, to love both their neighbours and God in the way that is illustrated by the story of the Good Samaritan.

To rectify this fallen condition, God took the initiative; becoming human in the man Jesus Christ, and giving his life so as to reconcile the world unto himself, attesting to it by raising Jesus bodily form the dead. We are then invited to repent and to live a new life out of the grace of God in the way that was demonstrated by Paul the Apostle in the New Testament.

Our human response to live out of this grace of God in the prospect of the fullness of the coming of the Kingdom of God and its full restoration of our humanity in Christ, should be one that is characterised by the same compassionate love and humility exhibited by Jesus in the flesh. However, its focus should be upon the future reality of a creation that is under the care, management, and direction of humankind as made in the image of God.

It is therefore form this kind of orientation that we should ponder upon and appreciate Stanley Kubrick’s film masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey. The key to such an interpretation, I suggest, is to be found in the way we interpret (a) the monoliths and (b) the conflict between HAL and the astronauts Dave Bowman and Frank Poole.

Thus we might consider the first appearance of the monolith as symbolising the way in which humankind are fashioned from ‘the dust of the ground’ – understood as the creational material from which we were put together. At the same time, the symbolism of the monolith speaks of the reality of our rebellious alienation from God in the depths of our hearts. This is exhibited in the way the ape-men use the bones as weapons for destruction and the rule over others that is characteristic of the ways in which humans have sought the consort and powers of false gods by which to lord it over others. This continues down to the present day, as modern terrorists are motivated by a thorough distortion of what it means to worship and serve God.

The discovery of the second monolith buried on the moon is a bit like the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead. It symbolises the invasion of our human space by a higher level of intelligent life that has the potential to change everything. It calls for a human response that draws upon the resources made available by this invasion into the human realm. The final appearance of the monolith confronts the reality of our present fallen condition in the world. However, the future hope is one that both fully appreciates the character of our humanity as made in God’s image. It also appreciates the extent of our fallen condition. Then, like babes in embryo, we look forward to the future of a new heavens and a new earth in which evil and rebellion against God and fellow-humans will be properly dealt with.

In the meantime, we live in a world that has become dominated by the idolatrous development of technology exhibited in the story of the conflict between HAL and the astronauts on Discovery One. This calls us to a serious reflection upon the present religious driving forces that shape not only our cultural landscape, but the whole of the reality of Gaia and beyond.

It is this spirit that I commend a reading of Petrus Simons’ summary of the recent book (still only available in the original Dutch) by Egbert Schuurman.

This is a mockup. Publish to view how it will appear live.